Environmental Art

The Centre for Local Prosperity understands and appreciates the need for not only scientific evidences of climate change, but also the need for personal feeling and experience of the dramatic changes happening on Earth. For this reason, the Centre has collaborations with a number of artists, writers and philosophers working in the intersection of climate change, culture, science and the arts. Bringing this wholistic right-brain-left-brain perspective to our changing world can be vital.

Regan Rosburg

Regan Rosburg is an artist and naturalist. Recently, her work has been an investigation into society’s collective grief, melancholia and mania which manifests as consumption and distraction. Rosburg is a professor at Metro State University, Denver. She is represented by William Havu Gallery, and Redline. Rosburg’s interest in both ecology and plastic pollution has taken her to many places around the globe. You can see her work here at www.reganrosburg.com.

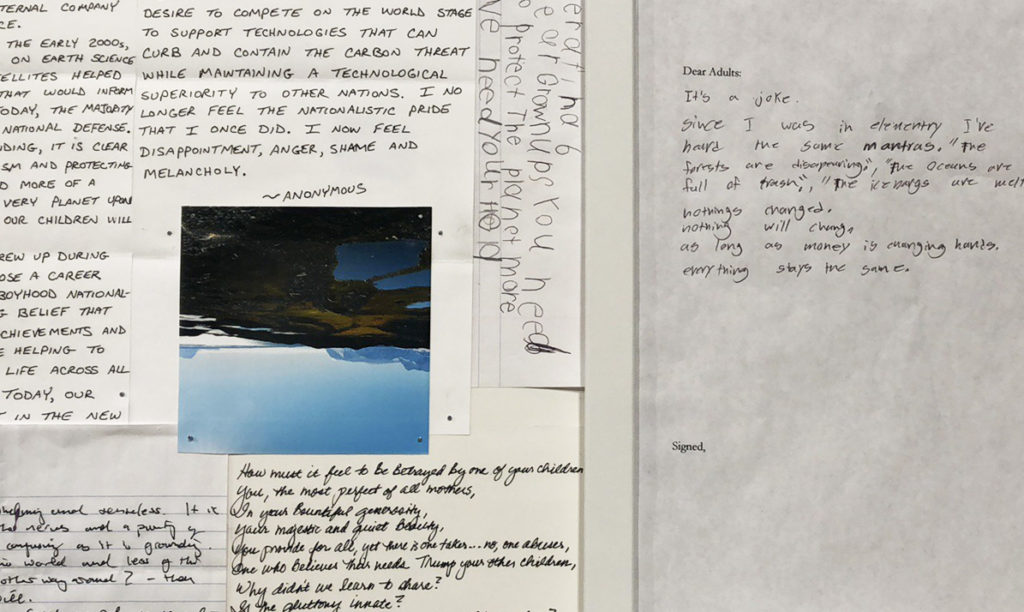

Omega was a collaboration between Rosburg and Hi-Tec Plastic recyclers in Aurora, Colorado. Hi-Tec donated 87 million plastic recycled pellets, which were then displayed in a warehouse in downtown Denver. Rosburg also coordinated with the recycling company to melt down HDPE plastic “runners” into her goose and pheasant wing molds, creating a haunting depiction reminiscent of oil slicks, burned branches, and life evolving from decay.

Upon close examination, Omega reveals signs of life blooming in her pools of clear resin, from vines and real insects to wasp nests and painted jellyfish. Rosburg’s intent in creating Omega was to provide participants (stripped of their shoes, socks and cellphones) a way to experience the overwhelming numbers of plastic pollution, to grieve the loss of a suffering world, and to conceive of personal choices one could implement for global change.

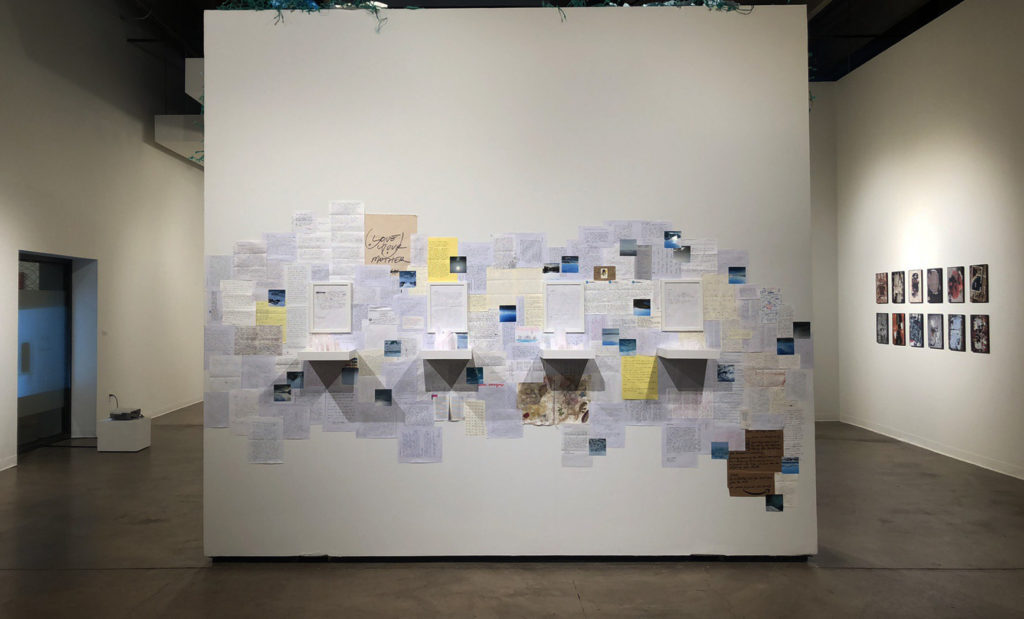

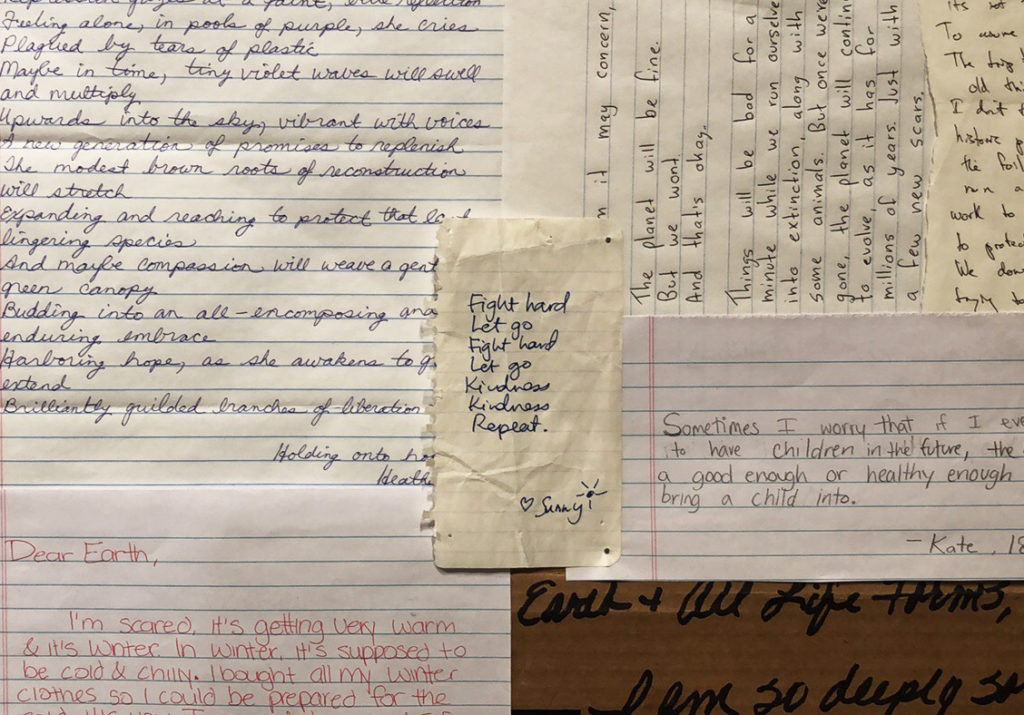

In 2017, I felt strongly that teenagers did not have a voice when it came to climate change, pollution, and ecological destruction. I asked them to write letters to adults that expressed their innermost feelings about what was happening to the planet. The letters were strikingly honest.

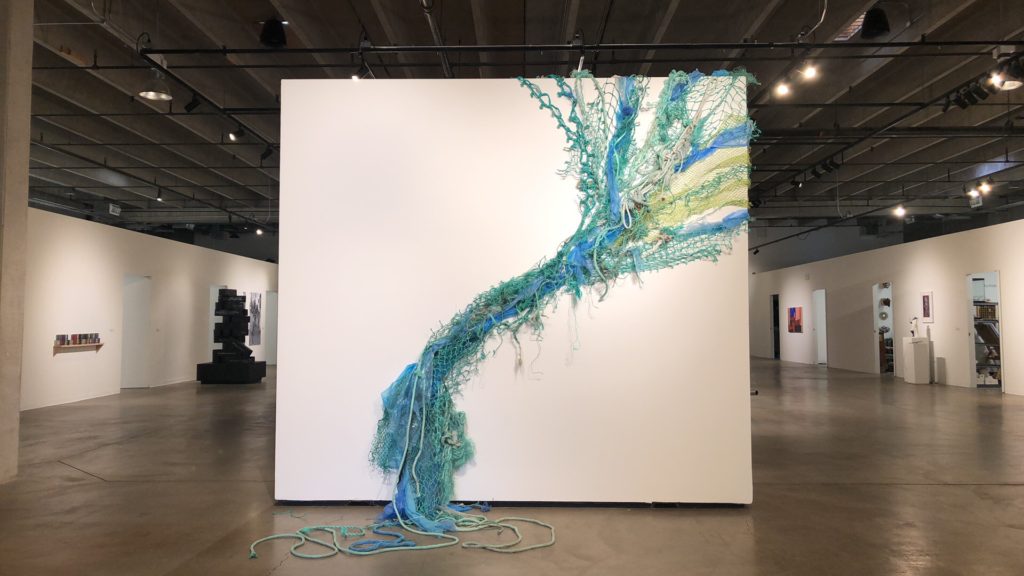

Two years later, I traveled to Svalbard with thirty other artists for the Arctic Circle Residency. The vast, expansive, pristine landscape of the Arctic affected each of us deeply. At the same time, we collected bags of garbage every time we made landfall. The inherent contradictions of the Arctic — felt by all of us — prompted me to expand the letter project to my comrades on the ship. Not surprisingly, I found their letters to be equally riveting and emotionally complex. We all wrestled with dichotomy: the guilt of traveling on an airplane to witness this incredible place, the awe-inspiring but worrisome sight of calving glaciers, and the fragile yet resilient life that burst forth in the Arctic summer. Video of plastic impact.

The project expanded further to residents and staff at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation (Virginia). Gardeners, librarians, biologists, art historians, landscapers, more artists, and art lovers all wrote personal letters voicing concern, love, fear, anger, wonder, guilt, melancholy, and cautious optimism.

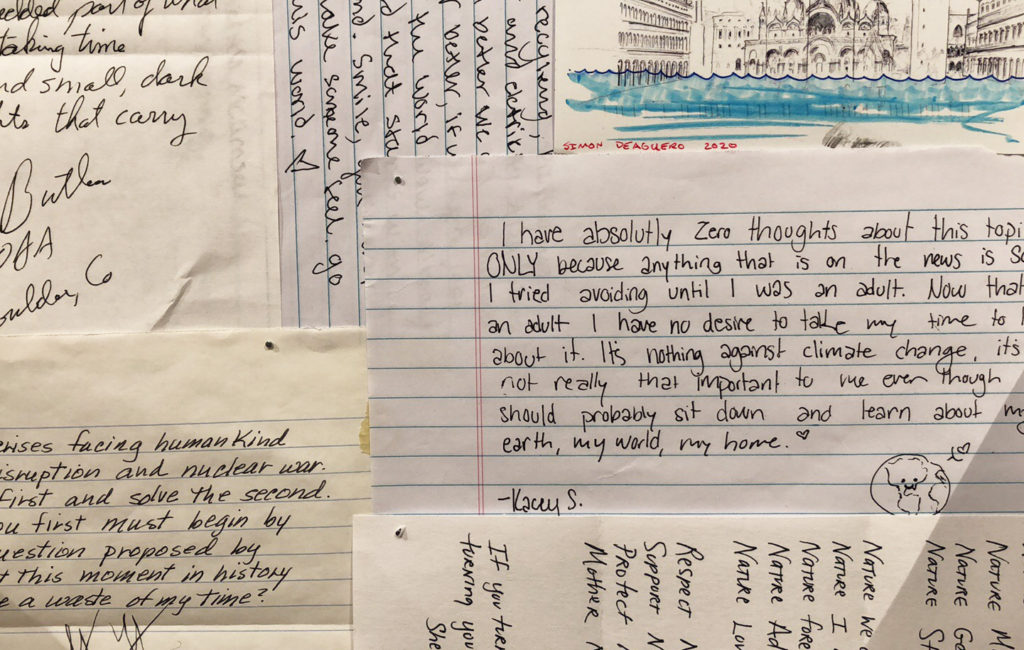

For Everything is Fine, I put out a public call for letters, and I received over a hundred. Children as young as six wrote about their concerns. Adults who had spent their entire careers studying climate change wrote poetic memories of how it used to be, while others vocalized their frustration under the new administration’s unspoken rule to not mention the words “climate change” and “global warming.”

Teachers wrote to students.

Students wrote to each other.

Others wrote to the future, to their parents, to whoever would listen.

The letters were diverse, representing everything from apathy to determination, from hostility to gratefulness, from fear to hope. I realized that putting pencil to paper unlocked a very personal, self-reflective place where the person was able to process inaudible emotions. Those who stood at the wall were able to experience the emotions of others.

Thus, Everything is Fine articulates two sides of one reality we currently face. One side of the wall is an example of consumption at any cost, the other side is a collection of personal inventories that expresses our connection to each other, to animals, to plants, and to our future. Ultimately, the work is neither about the plastic nor the letters. Instead, the materials on each wall represent our relationship to the planet: one of disconnection and one of connection.